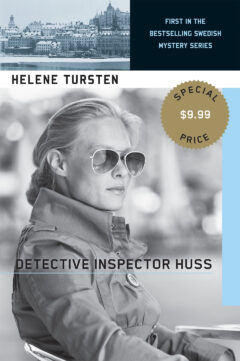

Detective Inspector Huss

By Helene Tursten. New York: Soho Press, 2003. 371 pages. ISBN: 9781616951115.

Kurt Wallander, Martin Beck, and now Irene Huss. Over the years, I have worked my way through the stories of these three fictional Swedish police detectives and have decided to revisit them, one by one.

This time, I am starting with Irene Huss, a character developed by writer Helene Tursten. She created 11 books in the series, beginning with Detective Inspector Huss, published originally in 1998. As in the late Henning Mankell’s Wallander books and Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö’s Beck stories, Tursten’s Huss works in a specific Swedish environment. Wallander serves in Ystad in southern Sweden and Beck is on the police force in Stockholm. Huss, meanwhile, lives and works in Sweden’s “second city” of Göteborg.

Huss is described as a 40-something woman who also is a judo expert. Her husband, Krister, is a chef and they are the parents of twin teenage girls, the rebellious Jenny and the studious Katarina. Throughout Detective Inspector Huss and in the other books in the series, the detective’s professional and family lives often intertwine.

Detective Inspector Huss begins with the apparent suicide of Richard von Knecht, a well-known and wealthy Göteborg businessman, who falls to his death from his fifth-floor apartment’s balcony. Before long, it’s clear that von Knecht was murdered. It is then up to Huss and the rest of the homicide division to figure out who killed him and why.

As other reviews have noted, Tursten touches on a variety of topics current in Swedish society, including an anti-immigrant and neo-Nazi undercurrent, which is made real for Huss when her daughter Jenny briefly joins a skinhead band and shaves her head to fit in with her new-found crowd. But the main plot centers on the murder case and how the police crack it. Much of the “action” in the book takes place in daily meetings in which detectives and other specialists gather to discuss progress on the case. This is, after all, in part a police procedural and meetings are, after all, part of modern police work. As a literary device, the meeting scenes also serve to give the reader a moment to reflect on what has happened so far in the story. In addition, Tursten uses the scenes to effectively point out the inequality between male and female police officers. For this, she uses the tension between two other detectives: the misogynistic Jonny Blom and the “cute, blond, and cuddly,” as well as independent, Birgitta Moberg.

Detective Inspector Huss is almost 20 years old, so there are a few minor moments when the novel shows its age, such as when Jenny states that she returned some skinhead music compact discs to her ex-boyfriend. I don’t imagine teenagers today would be listening to CDs.

Tursten’s book and others in the Irene Huss series were introduced to American audiences through New York-based Soho Press, publisher of a large number of international crime novels. (Trivia: Soho Press was co-founded by Latvian exile Juris Jurjevics, author of The Trudeau Vector, among other titles.)

The Irene Huss books also were adapted for television in a series of films produced by Sweden’s Yellow Bird Entertainment.

Next up for me in the series is Night Rounds, a book I have already read twice.

Accessed on 19 Apr 2024.

The article may be found online at https://straumanis.com/2017/detective-inspector-huss/.