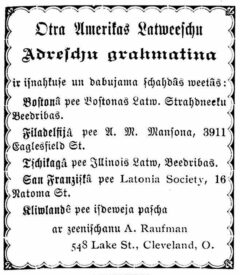

In October 1897, an immigrant in Cleveland published the first edition of an address book for Latvians living in the United States and Canada. A second edition appeared in early 1898.

Like many other publications by early Latvian immigrants to America, the address book is a bibliographic rarity. I am aware of only two copies: one is in private hands in the United States and the other is in a rare books collection in a library in Latvia.

The address book was a project of Alexander Raufman1 (Aleksandrs Raufmanis, 1866-1915), who immigrated to the United States about 1886. Raufman settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where he worked as a blacksmith, according to the federal census of 1900. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1894 and in 1896 married Latvian immigrant Wilhelmina Pilskam (Pilskalna). The couple had five children. Raufman died in December 1915 from injuries suffered in an accident while working for the railroad.

Raufman was responsible for printing several publications in the Latvian language: at least two editions of Amerikas latviešu adreses (American Latvian Addresses)2, at least three editions of a wall calendar3, a collection of poetry4, and the early socialdemocratic monthly Auseklis (Morning Star), which was edited in Boston by Dāvids Bundža.

Little else is known about Raufman. Even the most complete examination of the Latvian community of Cleveland, the book Mūsu mājas un patvērums5 (Our Home and Refuge), provides little information about him.

Digitizing the data in the address book offers an opportunity to get a better sense of the distribution of Latvian immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. Working from the second edition, the names and addresses of nearly 600 Latvian immigrants were entered into a spreadsheet, the addresses geocoded, and the data displayed on a Google map.

Not surprisingly, the map reveals that Latvian immigrants at the close of the 19th century were primarily located in northeastern U.S. cities, especially Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, but also in Midwestern cities such as Cleveland and Chicago.

However, some interesting bits also emerge, such as the concentration of Latvians near the docks in San Francisco, suggesting that a number of them came to America as sailors. Many listed the three-story building at 16 Natoma Street as their address, which also is where the Latonia Society — the first Latvian organization in San Francisco — was founded in 18976. A number of the early residences of Latvian immigrants would have been destroyed during the 1906 earthquake and the ensuing massive fire.

Then there are the outliers, such as Wilhelm Wagner, who in 1898 was living on remote Unga Island in Alaska. Several Latvian immigrants lived in Arizona, one in Minnesota, a few in Wisconsin.

As documentation of Latvian settlement in America, the address book presents several challenges:

- According to some contemporary estimates, the number of Latvians in North America by 1900 was about 4,000, so the second edition captures about 15 percent of the total. Undoubtedly, information collected by Raufman was self-reported as immigrants learned of the publication and decided that they wanted to be included.

- The directory is heavily male, which is a reflection of the overall tendencies of Latvian migration to America in the late 19th century, but also a reflection of the “head of household” reporting his address and not listing others in the family. Even Raufman’s own listing avoids mention of his spouse, Wilhelmina, or their children. Thus, hidden behind the nearly 600 listings are other family members.

- Street names are not permanent, so modern maps and geocoding systems may not help much when trying to locate an address from a century ago. For example, several Latvian men listed the Sailors Union in San Francisco as their address. That is, they listed a building at the corner of East and Mission streets. What was East Street is now a segment of The Embracadero. The structure known as the Audiffred Building (once the headquarters of the Sailors Union of the Pacific) still stands, being one of the few to survive the 1906 earthquake and fire. For the purposes of this map of Latvian immigrants, geocoding of many addresses had to be accomplished manually.

- Streets themselves are not permanent. Such was the case of Holly Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Holly was an alley between Brooks and Clark streets from its creation in 1868 to its closure in 1937, according to the Cambridge Buildings and Architects online database. The pleasant-sounding Hotel Holly, home to several Latvian immigrants in 1898, was a tenement on Holly Street.

- Even if streets do not change, addresses may. For example, Charles M. Purin7 (1872-1957) in 1898 listed his address as the German-English Teachers’ Seminary in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where he was a student. For the purposes of geocoding, the seminary’s pre-1930 address of 560 Broadway must be replaced with the modern address of 1020 N. Broadway. Historical trivia: Purin went on to become a professor of German. Purin Hall, a residence hall on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, is named for him.

- I can image that Raufman had to decipher more than one person’s difficult handwriting to determine a name or an address. For example, the entries for A. Enke and Edward Enke of LaGrange, Illinois, show them as living at 44 Wawla Avenue. Google cannot find a Wawla Avenue, and that’s because the Enkes lived on Waiela Avenue, as Cook County death records make clear. Similarly, the address book lists Andrew Kraul as living in Menekraune, Wisconsin, a place that did not exist. The Ventspils-born Kraul, according to his 1900 passport application8, was a lumberman living in Marinette, Wisconsin.

- The directory also has alphabetization and typographical inconsistencies; in a few cases lists only a name (for example, a mysterious “Mr. Conrade” under the C’s); and for some reason includes three Latvians in Brazil, two in South Africa, one in Jamaica, and another in England, even though no others beyond North America are mentioned.

Cleaning of the data — that is, verifying names, addresses, and coordinates — presents its own challenges. The year 1898 came two years before the next federal census, and in many cases immigrants who had temporary quarters in a location had moved on by 1900. Some Latvians had established themselves to a degree by 1900 and can be located in census schedules, but often not without difficulty. Take, for example, David Klein and eight other Latvian men who appeared in Raufman’s directory as living in Clifton Heights, Pennsylvania, which now is a suburb west of Philadelphia. Street addresses were not provided for them. However, stone mason David Klein (or Kline, as he was listed in the schedule) was counted in the 1900 census as living at 87 Baltimore St. He arrived in the United States in 1888, followed the next year by his wife and two children. His son, Edwin, probably was the E. Kleins of Clifton Heights listed in Raufman’s directory. Boarding in the home were four men and one female servant, all born in Russia. One of the men was carpenter Rudolph Kluge, who also appeared in Raufman’s directory.

At this point, the database and the resulting map still need work. The JavaScript behind the map’s display needs much improvement. Although the data have been cleaned to a certain degree, I continue to verify names and addresses, as well as to squash anomalies. And that, I know, will take months of reviewing census records, city directories, and other sources.

How to use the map

The map shows locations of 546 individuals for whom addresses were provided in the 1898 directory. In many cases — but not all — these addresses have been “cleaned” to provide accurate location data. Seven individuals with addresses outside North America were excluded, as were several for whom no location was provided or whose information could not be read because of damage to the original document.

In its initial view, the map displays clusters of markers. The numbers on the cluster icons show how many individuals are in the cluster. Clicking on a cluster will zoom in the map to a closer view, revealing both individual markers as well as smaller clusters. Continued clicking on clusters eventually reveals a solitary marker.

At this point, it is not possible to show all names that may be behind a marker. I have not yet found a satisfactory JavaScript solution that will allow a marker to display the location as a heading with the names of all individuals associated with that location appearing below. Thus, while the map represents 546 individuals, the user will not see 546 markers or names.

1. Also spelled Raufmann. In modern Latvian, his name would be written Aleksandrs Raufmanis. In some references, perhaps because of the difficulty of discerning between the Gothic letters “R” and “K,” his surname appears as Kaufmann.

2. While Raufman was based in Cleveland, the center of late-19th century Latvian publishing in the United States was Boston, where Jacob Sieberg (Jēkabs Zībergs) and the Rev. Hans Rebane in 1896 had started the newspaper Amerikas Vēstnesis. While they found the first edition of Raufman’s directory interesting, it was deemed to be incomplete and full of errors. “Amerikas latviešu adreses,” Amerikas Vēstnesis, November 15, 1897, p. 2.

3. The first edition of the calendar appeared in early 1894, according to L.J., “Vēstule iz Bostonas,” Baltijas Vēstnesis, February 21, 1894, p. 2. According to a correspondent for Tēvija, who had seen the calendar for 1897 being distributed at Christmastime in Boston, Raufman planned to change the publication to book format. However, the correspondent wrote (Tēvija, January 3, 1896, p. 7.), the calendar exhibited grammatical errors as well as a lack of proper Latvian letters: “In other words, the print shop still needs Latvian type and the calendar an editor.”

4. Reference to the poetry collection is found in Baltijas Vēstnesis, April 5, 1897, p. 2. The collection, titled Pirmais dzejoļu krājums Amerikā (First Poetry Collection in America), was described by a correspondent to the newspaper as lacking literary merit.

5. Arturs Rubenis, ed., Mūsu mājas un patvērums (Cleveland: Klīvlandes latviešu biedrība, 2000).

6. For more on early Latvian immigrants in San Francisco, see Raimond G. Slaidiņš, ed., Latvieši Sanfrancisko un tās apkārtnē (San Francisco: Ziemeļkalifornija latviešu biedrība, 2011), and Elga Zālīte, “Exploring the Library of Latvian Socialists in San Francisco, California: Activities of the Early Latvian Political Emigration, 1905-1917,” Latvijas Vēstures Institūta Žurnāls, 2014: 2(91), 6-92.

7. “Teacher of Languages Dies at 85,” La Crosse Tribune, September 19, 1957, p. 7.

8. “United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJP-HWKH : 16 March 2018), Andrew Kraul, 1900; citing Passport Application, Wisconsin, United States, source certificate #19428, Passport Applications, 1795-1905., Roll 543, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

Accessed on 20 Apr 2024.

The article may be found online at https://straumanis.com/2018/1898-address-book/.