Seven years ago, as part of a graduate certificate program in digital public humanities at George Mason University, I embarked on a project to trace the stories of 72 young Latvian Baptists from Philadelphia.

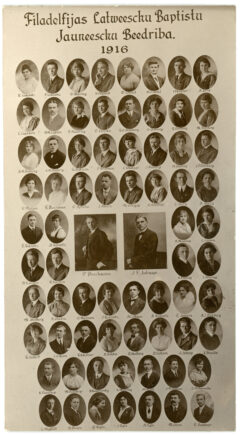

The project began when I discovered a wonderful postcard in the manuscript collection of the Rev. Peter Buschman (Pēteris Bušmanis, 1883-1970), which is held by the Immigration History Research Center Archives at the University of Minnesota. The postcard, created in 1916, showed the membership of the Philadelphia Latvian Baptist Youth Society.

The final course in the certificate program required creation of a digital history project. The postcard, I figured, was an excellent entry point into telling the broader story of Baptists from Latvia who had immigrated to the United States before the Second World War. The project also would allow me to learn Omeka, a content management system designed for digital history projects.

The website Latvian Baptists in America, 1890-1940 includes a digital exhibit devoted to the youth society and the postcard.

Now, seven years later, I am pausing further work on identifying all the members of the society. At this point, I have gathered at least basic information on 68 members, including the Rev. Buschman. The remaining four have eluded me, but perhaps someone reading this will be able to provide clues.

My goal in starting the project was to gather basic biographical information about each member: where they came from, what they did in Philadelphia and what became of them after 1916. For some of the members, this required little effort and was made easier by contacts I developed with descendants who provided more information. But for others, especially the remaining four, the work took months or years and taught me to think about historical detective work in different ways.

Here are some of the lessons of the project:

- Compared to women, tracking men was comparatively easy through the online genealogy databases provided by FamilySearch and Ancestry.com. The men usually were located quickly through census records, marriage certificates and petitions for naturalization. So, too, were women — but not always. As the period I was researching was in the midst of the First World War, some men could be located through their draft registration cards, which women did not complete. Men also could be found through veterans benefit records.

- Maintained by the National Library of Latvia, the online digital archive periodika.lv has been a valuable resource that has only gotten better over the past several years. It now has a new, cleaner interface and has added more periodicals, such as the old Boston newspaper, Amerikas Vēstnesis, which has been a great aid in my research. So, too, have digital newspaper collections in the U.S.

- It pays to be methodical, almost to a fault. So often as I was researching a particular individual, my search led me down a rabbit hole of relatives and tangents. Just because so much historical research can now be done digitally does not mean it should be done quickly or without a clear map. More than once I had to tell myself to slow down. (It’s a lesson I have tried to teach my undergraduates, too.)

- Others who have tried researching Latvian family history in America from the early 20th century or before know all too well that names often were represented by transliterating from the Gothic alphabet to the Latin alphabet. For example, what in modern Latvian would be Jānis Vītols would in pre-Second World War records most likely be Jahnis (or John) Wihtol. And that’s assuming Mr. Wihtol didn’t just translate his surname to English to become John Willow.

The digital history project focused on a specific artifact — the 1916 postcard. But in researching the youth society membership, I have developed a list of further ideas for research.

For example, the Latvian Baptists of Philadelphia initially concentrated in the western neighborhoods of the city, which was where their church was located. By the 1920s and 1930s, perhaps driven by employment opportunities, some had moved on to new concentrations, such as in Tinicum Township south of the city. Others headed even farther south — to Florida. Three of the four Mauring sisters — Alma, Selma and Tillie — did so. Their mobility, and that of other Latvian immigrants, intrigues me.

The Baptists also were not monolithic, differing theologically and politically. These differences were carried over from the old country and reshaped by the American context. The Rev. Buschman, who came to America from Liepāja, was influenced by the Social Gospel movement that he encountered while studying at the Rochester Theological Seminary in upstate New York. Some in the Philadelphia Latvian Baptist community certainly agreed with the idea of marrying faith with fighting social injustice. Others did not.

A number of male members of the youth society served in the military during the First World War (one, Adolph Kurmin, died on a battlefield in France). But at least one young man, James Frederick Yuhnags, declared on his draft registration card that he was a Baptist and therefore should be exempted from military service. It makes me wonder how prevalent this might have been in Philadelphia and other Latvian Baptist communities in America.

Many other seeds for research have been uncovered thanks to work on the youth society. But for now I will leave it behind — unless someone reading this has information on the stories of A. Azberg, A. Brown, E. Jansen or L. Janson.

Accessed on 22 Oct 2024.

The article may be found online at https://straumanis.com/2023/history-project-yields-stories/.